How to draw a covariance error ellipse?

Contents

Introduction

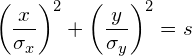

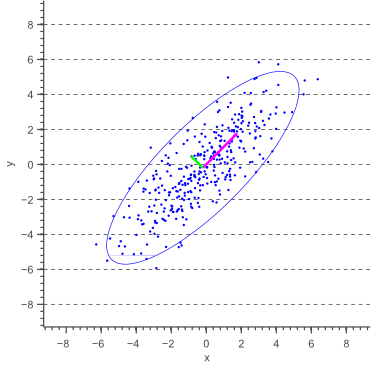

In this post, I will show how to draw an error ellipse, a.k.a. confidence ellipse, for 2D normally distributed data. The error ellipse represents an iso-contour of the Gaussian distribution, and allows you to visualize a 2D confidence interval. The following figure shows a 95% confidence ellipse for a set of 2D normally distributed data samples. This confidence ellipse defines the region that contains 95% of all samples that can be drawn from the underlying Gaussian distribution.

In the next sections we will discuss how to obtain confidence ellipses for different confidence values (e.g. 99% confidence interval), and we will show how to plot these ellipses using Matlab or C++ code.

Axis-aligned confidence ellipses

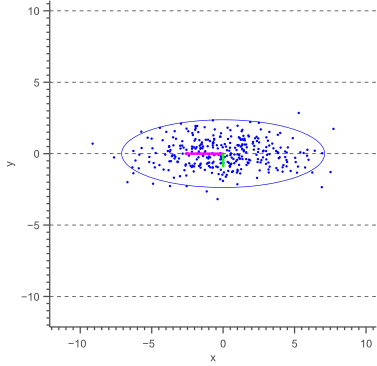

Before deriving a general methodology to obtain an error ellipse, let’s have a look at the special case where the major axis of the ellipse is aligned with the X-axis, as shown by the following figure:

The above figure illustrates that the angle of the ellipse is determined by the covariance of the data. In this case, the covariance is zero, such that the data is uncorrelated, resulting in an axis-aligned error ellipse.

| 8.4213 | 0 |

| 0 | 0.9387 |

Furthermore, it is clear that the magnitudes of the ellipse axes depend on the variance of the data. In our case, the largest variance is in the direction of the X-axis, whereas the smallest variance lies in the direction of the Y-axis.

In general, the equation of an axis-aligned ellipse with a major axis of length ![]() and a minor axis of length

and a minor axis of length ![]() , centered at the origin, is defined by the following equation:

, centered at the origin, is defined by the following equation:

(1) ![]()

In our case, the length of the axes are defined by the standard deviations ![]() and

and ![]() of the data such that the equation of the error ellipse becomes:

of the data such that the equation of the error ellipse becomes:

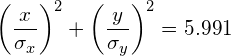

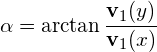

(2)

where ![]() defines the scale of the ellipse and could be any arbitrary number (e.g. s=1). The question is now how to choose

defines the scale of the ellipse and could be any arbitrary number (e.g. s=1). The question is now how to choose ![]() , such that the scale of the resulting ellipse represents a chosen confidence level (e.g. a 95% confidence level corresponds to s=5.991).

, such that the scale of the resulting ellipse represents a chosen confidence level (e.g. a 95% confidence level corresponds to s=5.991).

Our 2D data is sampled from a multivariate Gaussian with zero covariance. This means that both the x-values and the y-values are normally distributed too. Therefore, the left hand side of equation (2) actually represents the sum of squares of independent normally distributed data samples. The sum of squared Gaussian data points is known to be distributed according to a so called Chi-Square distribution. A Chi-Square distribution is defined in terms of ‘degrees of freedom’, which represent the number of unknowns. In our case there are two unknowns, and therefore two degrees of freedom.

Therefore, we can easily obtain the probability that the above sum, and thus ![]() equals a specific value by calculating the Chi-Square likelihood. In fact, since we are interested in a confidence interval, we are looking for the probability that

equals a specific value by calculating the Chi-Square likelihood. In fact, since we are interested in a confidence interval, we are looking for the probability that ![]() is less then or equal to a specific value which can easily be obtained using the cumulative Chi-Square distribution. As statisticians are lazy people, we usually don’t try to calculate this probability, but simply look it up in a probability table: https://people.richland.edu/james/lecture/m170/tbl-chi.html.

is less then or equal to a specific value which can easily be obtained using the cumulative Chi-Square distribution. As statisticians are lazy people, we usually don’t try to calculate this probability, but simply look it up in a probability table: https://people.richland.edu/james/lecture/m170/tbl-chi.html.

For example, using this probability table we can easily find that, in the 2-degrees of freedom case:

![]()

Therefore, a 95% confidence interval corresponds to s=5.991. In other words, 95% of the data will fall inside the ellipse defined as:

(3)

Similarly, a 99% confidence interval corresponds to s=9.210 and a 90% confidence interval corresponds to s=4.605.

The error ellipse show by figure 2 can therefore be drawn as an ellipse with a major axis length equal to ![]() and the minor axis length to

and the minor axis length to ![]() .

.

Arbitrary confidence ellipses

In cases where the data is not uncorrelated, such that a covariance exists, the resulting error ellipse will not be axis aligned. In this case, the reasoning of the above paragraph only holds if we temporarily define a new coordinate system such that the ellipse becomes axis-aligned, and then rotate the resulting ellipse afterwards.

In other words, whereas we calculated the variances ![]() and

and ![]() parallel to the x-axis and y-axis earlier, we now need to calculate these variances parallel to what will become the major and minor axis of the confidence ellipse. The directions in which these variances need to be calculated are illustrated by a pink and a green arrow in figure 1.

parallel to the x-axis and y-axis earlier, we now need to calculate these variances parallel to what will become the major and minor axis of the confidence ellipse. The directions in which these variances need to be calculated are illustrated by a pink and a green arrow in figure 1.

These directions are actually the directions in which the data varies the most, and are defined by the covariance matrix. The covariance matrix can be considered as a matrix that linearly transformed some original data to obtain the currently observed data. In a previous article about eigenvectors and eigenvalues we showed that the direction vectors along such a linear transformation are the eigenvectors of the transformation matrix. Indeed, the vectors shown by pink and green arrows in figure 1, are the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of the data, whereas the length of the vectors corresponds to the eigenvalues.

The eigenvalues therefore represent the spread of the data in the direction of the eigenvectors. In other words, the eigenvalues represent the variance of the data in the direction of the eigenvectors. In the case of axis aligned error ellipses, i.e. when the covariance equals zero, the eigenvalues equal the variances of the covariance matrix and the eigenvectors are equal to the definition of the x-axis and y-axis. In the case of arbitrary correlated data, the eigenvectors represent the direction of the largest spread of the data, whereas the eigenvalues define how large this spread really is.

Thus, the 95% confidence ellipse can be defined similarly to the axis-aligned case, with the major axis of length ![]() and the minor axis of length

and the minor axis of length ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() represent the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix.

represent the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix.

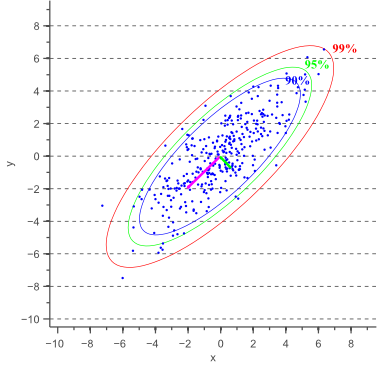

To obtain the orientation of the ellipse, we simply calculate the angle of the largest eigenvector towards the x-axis:

(4)

where ![]() is the eigenvector of the covariance matrix that corresponds to the largest eigenvalue.

is the eigenvector of the covariance matrix that corresponds to the largest eigenvalue.

Based on the minor and major axis lengths and the angle ![]() between the major axis and the x-axis, it becomes trivial to plot the confidence ellipse. Figure 3 shows error ellipses for several confidence values:

between the major axis and the x-axis, it becomes trivial to plot the confidence ellipse. Figure 3 shows error ellipses for several confidence values:

Source Code

Matlab source code

C++ source code (uses OpenCV)

Conclusion

In this article we showed how to obtain the error ellipse for 2D normally distributed data, according to a chosen confidence value. This is often useful when visualizing or analyzing data and will be of interest in a future article about PCA.

Furthermore, source code samples were provided for Matlab and C++.

If you’re new to this blog, don’t forget to subscribe, or follow me on twitter!

There is a little mistake in the text (not in the matlab source code), the major (minor) axis are 2*sqrt[\lambda_1 * 5.991] (2*sqrt[\lamba_2 * 5.991]). The axis lengths are related with standard deviations, whereas \lambda_1 and \lambda_2 come from the covariance matrix (STD = sqrt(variance))

You are right, tnx for spotting this! I fixed it now in the text.

I love you man, you saved my life with this blog. Don’t stop posting stuff like this.

Thanks Vincent! I find very useful your post!

One question, If I want to know if an observation is under the 95% of confidence, can I replace the value under this formula (matlab):

a=chisquare_val*sqrt(largest_eigenval)

b=chisquare_val*sqrt(smallest_eigenval)

(x/a)^2 + (y/b)^2 <= 5.991 ?

Thanks

Hi Alvaro, your test will return true for all data points that fall inside the 95% confidence interval.

Hi Vincent, thanks for your answer

Very helpful. Thanks. How is it different for uniformly distributed data ?

Thank you very much. Your post is very useful!

I have a question in the matlab code.

What the (chisquare_val = 2.4477)?

I don’t know the meaning 2.4477.

Hi Kim, this is the inverse of the chi-square cumulative distribution for the 95% confidence interval. In Matlab you can calculate this value using the function chi2inv(), or in python you can use scipy.stats.chi2. Alternatively you can find these values precalculated in almost any math book, or you can use an online table such as https://people.richland.edu/james/lecture/m170/tbl-chi.html.

Hi

How can I calculate the length of the principal axes if I get negative eigenvalues from the covariance matrix?

I think they can’t be negative. Variance can’t be negative, and there are limits to the covariance, though it can be negative.

In cases where the eigenvalues are close, they might go negative due to rounding error in the calculation.

Vincent, you are great, thank you. I’m naming my first born after you!

Hi Vincent,

Is this method still applicable when the centre of the ellipse does not coincide with the origin of the coordinating system?

Thank you,

Since additive effects don’t influence your confidence interval, you can simply subtract the mean from the data such that is becomes centered, then calculate the confidence ellipse parameters, and then add the mean again to shift the ellipse centroid to the right location.

Hi,

your Post helped me a lot! Thx! Since I needed the error ellipses for a specific purpose, I adapted your code in Mathematica.

If you don’t mind, I ‘d like to share it:

(*Random Data generation*)

s = 2;

rD = Table[RandomReal[], {i, 500}];

x = RandomVariate[NormalDistribution[#, 0.4]] & /@ (+s rD);

y = RandomVariate[NormalDistribution[#, 0.4]] & /@ (-s rD);

data = {x, y}\[Transpose];

(*define error Ellipse*)

ErrorEllipse[data_, percLevel_, points_: 100] :=

Module[

{eVa, eVec, coors, dchi, thetaGrid, ellipse, rEllipse},

{eVa, eVec} = Eigensystem@Covariance[data];

(* Get the coordinates of the data mean*)

coors = Mean[data];

(*Get the perc [%] confidence interval error ellipse*)

dchi = \[Sqrt]Quantile[ChiSquareDistribution[2], percLevel/100];

(* define error ellipse in x and y coordinates*)

thetaGrid = Table[i, {i, 0, 2 \[Pi], 2 \[Pi]/99}];

ellipse = {dchi \[Sqrt]eVa[[1]] Cos[thetaGrid],

dchi \[Sqrt]eVa[[2]] Sin[thetaGrid]};

(* rotate the ellipse and center ellipse at coors*)

rEllipse = coors + # & /@ (ellipse\[Transpose].eVec)

];

(* visualize results*)

percentOneSigma = 66.3;

percentTwoSigma = 95.4;

Show[

ListPlot[data],

ListLinePlot[ErrorEllipse[data, percentOneSigma],

PlotStyle -> {Thick, Red}],

ListLinePlot[ErrorEllipse[data, percentTwoSigma],

PlotStyle -> {Thick, Blue}],

ListPlot[{Mean[data]}, PlotStyle -> {Thick, Red}]

]

Best,

bashir

Thanks a lot for your contribution, Bashir!

Hi, thanks a lot for the code. Just a little bit comment; in general chisquare_val=sqrt(chi2inv(alpha, n)) where alpha=0.95 is confidence level and n=degree of freedom i.e, the number of parameter=2.

here we go a little bit change to make the code a little bit more beautiful

Cheers,

Meysam

clc

clear

% Create some random data with mean=m and covariance as below:

m = [10;20]; % mean value

n = length(m);

covariance = [2, 1; 1, 2];

nsam = 1000;

x = (repmat(m, 1, nsam) + sqrtm(covariance)*randn(n,nsam))’;

y1=x(:,1);

y2=x(:,2);

mean(y1)

mean(y2)

cov(y1,y2)

data = [y1 y2];

% Calculate the eigenvectors and eigenvalues

%covariance = cov(data);

[eigenvec, eigenval ] = eig(covariance);

% Get the index of the largest eigenvector

[largest_eigenvec_ind_c, r] = find(eigenval == max(max(eigenval)));

largest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:, largest_eigenvec_ind_c);

% Get the largest eigenvalue

largest_eigenval = max(max(eigenval));

% Get the smallest eigenvector and eigenvalue

if(largest_eigenvec_ind_c == 1)

smallest_eigenval = max(eigenval(:,2));

smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:,2);

else

smallest_eigenval = max(eigenval(:,1));

smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(1,:);

end

% Calculate the angle between the x-axis and the largest eigenvector

phi = atan2(largest_eigenvec(2), largest_eigenvec(1));

% This angle is between -pi and pi.

% Let’s shift it such that the angle is between 0 and 2pi

if(phi < 0)

phi = phi + 2*pi;

end

% Get the coordinates of the data mean

% Get the 95% confidence interval error ellipse

%chisquare_val = 2.4477;

alpha = 0.95;

b = chi2inv(alpha, n);

theta = linspace(0,2*pi,100);

X0=m(1);

Y0=m(2);

a=sqrt(b*largest_eigenval);

b=sqrt(b*smallest_eigenval);

%Define a rotation matrix

R = [ cos(phi) sin(phi); -sin(phi) cos(phi) ];

Q=[ a*cos( theta);b*sin( theta)]';

%let's rotate the ellipse to some angle phi

r_ellipse = Q * R;

% Draw the error ellipse

plot(r_ellipse(:,1) + X0,r_ellipse(:,2) + Y0,'g','linewidth',2)

hold on;

% Plot the original data

plot(data(:,1), data(:,2), 'o');

g=plot(m(1),m(2),'o','markersize', 10);

set(g,'MarkerEdgeColor','r','MarkerFaceColor','r')

mindata = min(min(data));

maxdata = max(max(data));

Xlim([mindata-3, maxdata+3]);

Ylim([mindata-3, maxdata+3]);

hold on;

%Plot the eigenvectors

quiver(X0, Y0, largest_eigenvec(1)*sqrt(largest_eigenval), largest_eigenvec(2)*sqrt(largest_eigenval), '-m', 'LineWidth',2);

quiver(X0, Y0, smallest_eigenvec(1)*sqrt(smallest_eigenval), smallest_eigenvec(2)*sqrt(smallest_eigenval), '-g', 'LineWidth',2);

hold on;

%Set the axis labels

xlabel(' Xdata ','interpreter','latex','fontsize',18)

ylabel('Ydata ','interpreter','latex','fontsize',18)

set(gca, 'fontsize',16);

Great addition, Meysam, tnx!

Shouldn’t chi square value 5.9915 instead of 2.4477?

Hello

Thank you for the useful information.

I’m not sure if the coordinates of the eigenvector are used correctly in the cv code.

In the cv documentation there is information:

“eigenvectors – output matrix of eigenvectors; it has the same size and type as src; the eigenvectors are stored as subsequent matrix rows, in the same order as the corresponding eigenvalues.”

If the vectors are in rows I would expect:

double angle = atan2(eigenvectors.at(0,1), eigenvectors.at(0,0));

instead of

double angle = atan2(eigenvectors.at(1,0), eigenvectors.at(0,0));

In the cv documantation there is also information:

“Note: in the new and the old interfaces different ordering of eigenvalues and eigenvectors parameters is used.”

Could you please comment on this.

Best wishes

Adam

Hi Adam, you are right! Thanks for spotting this. I just updated the code.

Hello everyone,

I am trying to do this plots in python, I have found the following code:

x = [5,7,11,15,16,17,18]

y = [8, 5, 8, 9, 17, 18, 25]

cov = np.cov(x, y)

lambda_, v = np.linalg.eig(cov)

lambda_ = np.sqrt(lambda_)

from matplotlib.patches import Ellipse

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ax = plt.subplot(111, aspect=’equal’)

for j in xrange(1, 4):

ell = Ellipse(xy=(np.mean(x), np.mean(y)),

width=lambda_[0]*j*2, height=lambda_[1]*j*2,

angle=np.rad2deg(np.arccos(v[0, 0])))

ell.set_facecolor(‘none’)

ax.add_artist(ell)

plt.scatter(x, y)

plt.show()

which draws a 1, 2 and 3 standard deviation ellipses.

I dont understand to which percentage (95 % etc) does each j corresponds. Could anyone please give me a hint?? Cheers and thanks,

Yisel

A 1-standard deviation distance corresponds to a 84% confidence interval. Two standard deviations correspond to a 98% confidence interval, and three standard deviations correspond to a 99.9% confidence interval. (https://www.mathsisfun.com/data/images/normal-distrubution-large.gif)

Hi! many thanks for this helpful post: just one more question about this code (that I’m using too).

According to what you are saying, the variable j correspond to the z-score: is it correct? then for 95% CI we should use j=1.96.

Why we shoulld use z-score instead of Chi (as you explained in your post)?

Many Thanks

Hi Vincent, thanks for a great post. I’m a little bit curious, but the mahalanobi distance is more or less the same principle just for higher dimensions? Calling it density contours, error ellipses, or confidence regions? Thanks!

Hi Sonny, I’m not sure what you mean here. Mahalanobis distance corresponds to the Euclidean distance if the data was whitened. In other words, Mahalanobis distance considers the variance (and covariance) of the data to the normalize the Euclidean distance.

Hi Vincent, what a great article, thank you very much.

Regarding your comment, would you elaborate on that as I’m not getting what you meant. Based on my understanding, all point lie on the same ellipse have the same Mahalanobis distance and consequently Chi-square probability. Is that right?

Great write up. I was wondering if you have a reference for this method?

Hi Chris, thanks a lot! I’m afraid I don’t really have a reference, but I’m pretty sure you should be able to find this method in a statistics text book.

Strangely in all my stats books and probability books they do not discuss this…

square root of chi-square value (i.e. 5.991).

Hi Vincent, the post was excellent. Could you include a short comment under what conditions the ellipsis switch to have a “banana shape”? That is common in cosmological data analysis. Thank you.

Thanks for this post! I am trying to implement this method in javascript.

http://plnkr.co/edit/8bONVq?p=preview

The errorEllipse function is in the “script.js” file. The most obvious issue I see with the results of my current attempt is that scale of the ellipse is too large. It’s possible there are other issues as well.

I am getting the expected values from the Math.sqrt(jStat.chi.inv()). I think it’s possible I’m not handling the eigenvalues properly.

I haven’t been able to figure out what’s wrong yet, and haven’t had a chance to test the openCV code to see which values are wrong. I’m using the libraries numeric.js for the eigenvectors and values, jstat, and d3 for plotting. Any suggestions appreciated. Test data can be changed by editing testData.js

I think there’s a bug in your MATLAB code:

smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(1,:);

should be:

smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:,2);

It just happens that in your example, they are the same, but the are not in general.

An extremely well written article!!

But what if the data points have errors on them? How does one plot error ellipses then?

This is really useful. What book can I find these derivations in?

The math is a combination of analytic geometry and linear algebra.

Yes, but in a methods section of a paper it is nice to have a book/paper to cite when there isn’t space to do the derivation.

OK for those that want a source:

Johnson and Wichern (2007) Applied Multivariate Statistical Anlaysis (6th Ed) See Chapter 4 (result 4.7 on page 163).

They have a very nice intuitive overview, and actually prove the result. Strange that my two other elementary multi-d stats books have no mention of this important result, much less deriving it.

Tnx a lot for the reference, Eric. To be honest, I wouldn’t have known where to look :). As Glenn mentioned though, this post is simply a combination of some geometry and linear algebra. Not sure if any math book should necessarily discuss this specific use case.

The equation for an ellipse should be in any book on Analytic Geometry.

The Eigenvalues for a 2×2 matrix should be in most books on linear algebra.

It seems likely that neither field will cover the other enough to combine them, but you should have books for both on your shelf. Analytic geometry might not be covered in the usual undergraduate engineering series, but linear algebra should be. (It is also probably one that students don’t learn as well as they should.)

Teaching cross-disciplinary fields has always been a problem. Physics doesn’t teach the math that students are supposed to learn from the math department. Sometimes they need it before the math department gets around to it.

I got interested in this for a physics problem, not a statistics problem. It is the same solution as for phase space of a beam, which is related to the correlation between position and momentum for particles in a beam.

If only it were as simple as knowing eigenvectors and the equation for an ellipse! At any rate, for those fields that don’t want you to re-derive the wheel in the methods section, it will be helpful to have a concrete citation to use.

Didn’t mean to sidetrack the thread, this is a fantastic post in a great site, it’s just been bugging me for a few months that I was missing a scholarly citation. Thanks again for the great reference post!

Thanks again for the great reference post!

I didn’t mean to say that it was easy. One complication is that you need parts of unrelated fields. Not being an expert in either, it took me some hours to derive it, given the explanation here.

Thank for a great article, I’ve bookmarked your site.

You don’t actually need statistical tables to calculate S.

S=-2ln (1-P)

It is a very complete and simple explanation. My only doubt is if we must order the eigenvalues. If we call the ellipses axes a and b, this means that the axis a will be always larger then b? Is it not possible the inverse situation?

Hi,

I am a beginner both at statistics and I am trying to this using Matlab. Thank you so much for this post, it is extremely helpful.

However, I have a couple of questions…

(1) In the matlab code, what does the s stand for (s – [2,2])? What are these values?

(2) Further down you have a [largest_eigenvec_ind_c, r]…. what is the ind_c,r mean?

(3) For the chi-square value, for my understanding if I want to have a 95% confidence interval with two directions of freedom my value would be 5.991. Is this correct?

Apologies if these are very basic but it would be a great help to me to understand the code so I can adapt it to my dataset. Thanks!

Hi. Thanks a lot for the tutorial and detailed explanation. Great Work.

I had a go at hacking together a 3D version in MATLAB. Code below just in case anyone is interested.

%based on http://www.visiondummy.com/2014/04/draw-error-ellipse-representing-covariance-matrix/

clear;

close all;

% Create some random data

s = [1 2 5];

x = randn(334,1);

y1 = normrnd(s(1).*x,1);

y2 = normrnd(s(2).*x,1);

y3 = normrnd(s(3).*x,1);

data = [y1 y2 y3];

% Calculate the eigenvectors and eigenvalues

covariance = cov(data);

[eigenvec, eigenval ] = eig(covariance);

% Get the index of the largest eigenvector

%[largest_eigenvec_ind_c, ~] = find(eigenval == max(max(eigenval)));

[B, largest_eigenvec_ind_c] = sort(max(eigenval),’descend’);

largest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:, largest_eigenvec_ind_c(1));

% Get the largest eigenvalue

largest_eigenval = max(max(eigenval));

% % Get the smallest eigenvector and eigenvalue

% if(largest_eigenvec_ind_c == 1)

% smallest_eigenval = max(eigenval(:,2));

% smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:,2);

% else

% smallest_eigenval = max(eigenval(:,1));

% smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:,1);

% end

% Calculate the angle between the x-axis and the largest eigenvector

angle = atan2(largest_eigenvec(2), largest_eigenvec(1));

angle2 = atan2(largest_eigenvec(3), largest_eigenvec(1));

angle3 = atan2(largest_eigenvec(3), largest_eigenvec(2));

% % This angle is between -pi and pi.

% % Let’s shift it such that the angle is between 0 and 2pi

% if(angle < 0)

% angle = angle + 2*pi;

% end

% if(angle2 < 0)

% angle2 = angle2 + 2*pi;

% end

% if(angle3 < 0)

% angle3 = angle3 + 2*pi;

% end

% Get the coordinates of the data mean

avg = mean(data);

% Get the 95% confidence interval error ellipse

chisquare_val = 2.4477;

theta_grid = linspace(0,2*pi);

phi = angle;

X0=avg(1);

Y0=avg(2);

Z0=avg(3);

a=chisquare_val*sqrt(largest_eigenval);

b=chisquare_val*sqrt(max(eigenval(:,largest_eigenvec_ind_c(2))));

c=chisquare_val*sqrt(max(eigenval(:,largest_eigenvec_ind_c(3))));

hold on;

%create an ellipsoid.

[x,y,z] = ellipsoid(X0,Y0,Z0,a,b,c,40);

% create the rotation matrix;

R=createEulerAnglesRotation(angle, angle2, angle3);

r_ellipse = [x(1,:);y(1,:);z(1,:)]' * R(1:3,1:3);

h=surf(x,y,z,'EdgeColor','none','FaceAlpha',0.1);

t = hgtransform;

set(h,'Parent',t)

ry_angle = -15*pi/180; % Convert to radians

R = createEulerAnglesRotation(-angle2, -angle3, angle); % roll, pitch, heading

set(t,'Matrix',R);

% Plot the original data

plot3(data(:,1), data(:,2), data(:,3), '.');

mindata = min(min(data));

maxdata = max(max(data));

xlim([mindata-3, maxdata+3]);

ylim([mindata-3, maxdata+3]);

% % Plot the eigenvectors

% quiver(X0, Y0, largest_eigenvec(1)*sqrt(largest_eigenval), largest_eigenvec(2)*sqrt(largest_eigenval), '-m', 'LineWidth',2);

% quiver(X0, Y0, smallest_eigenvec(1)*sqrt(smallest_eigenval), smallest_eigenvec(2)*sqrt(smallest_eigenval), '-g', 'LineWidth',2);

% % Set the axis labels

hXLabel = xlabel('x');

hYLabel = ylabel('y');

hZLabel = zlabel('z');

hold off

Hi! Great work also for you!

Do you know the case where one of the data y1, y2 or y3 are non normal?

Thank you in advance!

Great work. Can you add something: Color all data values RED inside 95% ellipse and all data values outside BLUE (see post from June 16, 2014). The following code attempts this but is NOT working:

% See if (x/a)^2 + (y/b)^2 <= 5.991 ?

d = (data(:,1)./a).^2+(data(:,2)./b).^2;

e1=find(d=s);

plot(data(e1,1), data(e1,2), ‘r.’);hold on; %Plot data inside ellipse

plot(data(e2,1), data(e2,2), ‘b.’);hold on; %Plot data outside ellipse

plot(r_ellipse(:,1) + X0,r_ellipse(:,2) + Y0,’k-’);hold off; %Plot ellipse

The following colors the data points RED/BLUE depending on if the datapoint is inside/outside of the ellipse

Ntmp = size(data,1);

datatmp = (data – repmat([X0 Y0],Ntmp,1))*R’;

dis1 = (datatmp(:,1)/a).^2+(datatmp(:,2)/b).^2;

e1 = find(dis1 1);

plot(data(e1,1),data(e1,2),’r.’);hold on;

plot(data(e2,1),data(e2,2),’b.’);hold on;

xpct = size(e1,1)/Ntmp;

fprintf(‘%5.3f pct inside ellipse\n’,xpct);

Sorry…copy/paste not working. The code needs:

e1 = find(dis1 1);

e1 = find(dis1 1);

Can I use this method with a data that is not normal distribution?

Hi

First, thank you for the beautiful article.

Second, I will appriciate any help with my problem. My ellipse seems to be much bigger than what it suppose to be I believe it’s because my data is not normal distribution but it is asymetric distribution.

Someone found a way to change the code so it will fit to this kind of distribution.

maybe usinf t-student test and than the degree of freedom is n-1 of the amount of data? can someone tell me if it’s seems right to do it?

thanks

I have one question. If we want to calculate the area of this ellipse what should we do?

Hi, I have to evaluate the eccentricity of the ellipse, so I need the value of each axis, how can i find them? maybe they are the same as eigenvalues?!

Great Work!

What about the case that one of our datasets are non normal distributed?

Thank you in advance!

Vincent – thanks a lot for your article. It become clear for me right now how it works for normal distribution. But what if your data are not normal? What would you do than?

Hi,

Great tutorial!

Aren’t the eigenvectors given in the columns?

So why is it in the MATLAB code that the smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(1,:); instead of smallest_eigenvec = eigenvec(:,1)?

Thanks!

Hello!! Thanks a lot for the code!

How can I calculate the area of the drawned error ellipse?

I don’t think you need to monkey around with rotations and what not. I think you can just do

avg’ + chisquare_val * (sqrt(eigenval(1,1))*eigenvec(:,1)*cos(theta_grid) + sqrt(eigenval(2,2))*eigenvec(:,2)*sin(theta_grid));

once you have defined chisquare_val, avg, theta_grid, and eigenval and eigenvec.

My half minor axis is a negative value and the square root returns a “nan”.